Archive for the ‘growing and gathering’ Category

growing and gathering – the benefits of eating ‘very local’ foods

In 2007, Alisa Smith and J.B. MacKinnon embarked on a year-long experiment in eating local. Their book, The 100 Mile Diet – A Year of Local Eating, introduced many to the idea of obtaining their food from nearby sources. It reminded people about the thousands of kilometers our food has to travel to make it to our tables. It pointed out some of the barriers to ‘eating local’ and showed how, with a little ingenuity and effort, our diets could be more environmentally conscious and sustainable.

Eating local foods is a sound choice in our illogical world. It supports local farmers and producers. It mitigates some of the energy costs associated with moving food hundreds of miles to the consumer. It honors our origins and connects us to our ancestors who lived their lives more simply and locally.

Into this concept of eating local, I include the idea of eating wild foods whenever possible. My mother grew up in a time when bulging grocery carts were unheard-of. Without subscribing to any particular theory of eating local, she supplemented her food with wild edibles as a matter of habit. In addition to using rhubarb and currents from her garden, she picked berries when they were in season, tried to convince her family to join her in eating dandelion greens and sour dock, and showed us how to pick spruce gum from spruce trees as a chewy treat.

Eating ‘very local’ has many benefits. The edible plants growing right outside our doors are filled with nutrients, many are very palatable, even delicious, and they are present in great variety, and in all seasons. They are free and are easy to harvest and prepare. Picking berries or chewing spruce gum puts us in touch with nature and helps us to understand our role as a member of the ecosystem. It honors the people who came before us and helps us connect with the way our parents and grand-parents lived their lives. Identifying and picking wild plants for food is an enjoyable activity and a way to show your children how to be thrifty, engaged members of the ecosystem.

In an upcoming post, I will look at some of the ethical issues around using wild plants as food.

~

~

six bottles of jam

~

I reach up, for a cluster of pin cherries

and stop –

above me, my grand-mother’s hand

dry as a page from her recipes,

age-spotted, worried at the edges

her ankles are swollen, but she is determined –

enough berries for a half-dozen

bottles of pin cherry jam

~

~

© Jane Tims 2012

Warning: 1. never eat any plant if you are not absolutely certain of the identification; 2. never eat any plant if you have personal sensitivities, including allergies, to certain plants or their derivatives; 3. never eat any plant unless you have checked several sources to verify the edibility of the plant.Rough Bedstraw (Galium asprellum Michx.)

Rough Bedstraw (Galium asprellum Michx.) is a common sprawling weed. It forms a tangle across low pastures, brooksides and ditches. The tangle looks springy and comfortable, the perfect mattress stuffing, but feels rough and sticky when rubbed backwards from stem to flowers, due to the plant’s rasping, hooked prickles.

Other names for bedstraw are Cleavers and, in French, gaillet. The generic name is from the Greek gala meaning ‘milk’, since milk is curdled by some species.

Rough Bedstraw is one of a number of common Galium species. They all have the same general habit… small narrow leaves are arranged in whorls of six or eight around the stem. They are all useful plants. They were used as stuffing because of their physical characteristics and because the smell of the dried plant repels fleas.

To identify the species of Galium mentioned below:

~ smell the plant in question

~ count the leaves

~ look for the color of the flowers

~ determine if the plant is rough or smooth

~

~

Galium asprellum Michx.

Rough Bedstraw has its leaves in sixes, and is rough with recurved bristles. Its flowers are white. This species has weak stems and reclines on other vegetation. Asprellum means ‘somewhat rough’. It has been used to stuff mattresses.

Galium triflorum Michx.

Sweet-scented Bedstraw or Fragrant Bedstraw grows in forested areas. It has white flowers arising along the stem and its leaves in sixes. It reclines and clings, but is not as bristly as Rough Bedstraw. Fragrant Bedstraw is used for stuffing mattresses and has the smell of vanilla when it dries.

Galium verum L.

Lady’s Bedsraw or Yellow Bedstraw has yellow flowers borne at the top of the upright stem, and leaves in sixes or eights. The plant is hairy but not clinging. The word verum means ‘true’, derived from the Christian tradition that Yellow Bedstraw lined Jesus’ manger at Bethlehem. The roots also make a red or yellow dye.

Galium aparine L.

Cleavers, Goose-grass, Stickywilly, or (in Ireland) Robin Run the Hedge is bristly and has white flowers and leaves in eights. Aparine is the old generic name and probably means to ‘scratch, cling or catch’. The young shoots can be cooked as greens or used as a salad. The nuts are roasted and ground for a coffee substitute.

Galium mollugo L.

White Bedstraw, Hedge Bedstraw, or Wild Madder has white flowers and its leaves mostly in eights. It is smooth, without bristles and stands upright. A red dye is made from the roots. Its leaves are edible as a potherb or salad. It has a mildy astringent taste.

Most of the Galium along the roadsides in our area is Wild Madder (Galium mollago L.).

~

Rough Bedstraw

(Galium asprellum Michx.)

~

Our mattress is lumpy, as though stuffed

with Rough Bedstraw, fragrant as new sheets

but uncomfortable

~

I sleep poorly

and a spring sticks in my back,

just where arthritis begins, along the spine

~

Small back-pointed bristles

thwart my turning, bed-clothing tacky

on this humid night

~

~

© Jane Tims 2012

Warning: 1. never eat any plant if you are not absolutely certain of the identification; 2. never eat any plant if you have personal sensitivities, including allergies, to certain plants or their derivatives; 3. never eat any plant unless you have checked several sources to verify the edibility of the plant.growing and gathering

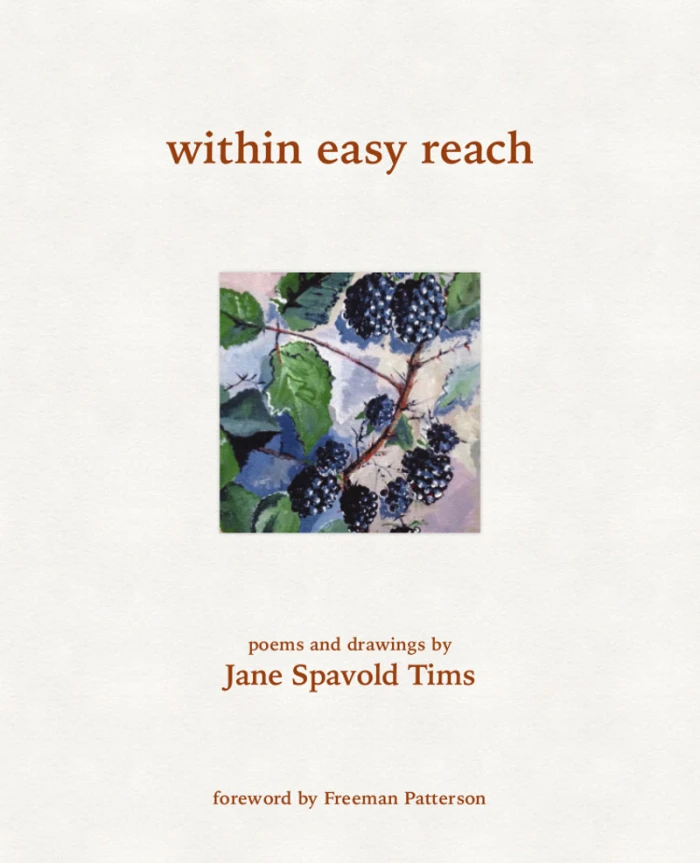

Many of my recent posts are associated with my writing project, ‘growing and gathering’. My aim is to write a poetry manuscript about collecting and producing local foods. So far, I have concentrated on ‘edible wild plants’ in my blog, but the full scope of the project will include poems on gardening and other aspects of aquiring local foods.

My process so far has included research into a particular wild plant, a trip to see it in the wild and perhaps gather it for eating, a piece of prose on the characteristics of the plant, a pencil drawing (becoming more and more a part of my thought process), and a poem or poems about the edible plant.

As my project progresses, I am generating many poems. I am also starting to think about how I will assemble this information into a manuscript.

One of the first steps toward assembling the manuscript is to decide what themes are emerging. This will help me decide how the poems relate to one another, as well as identify the gaps.

Major themes so far are:

~ companionship (for example, picking berries with a friend)

~ competition (for example, trying to get those hazelnuts before the squirrels)

~ time (this includes historical uses of wild edibles, as well as seasonal and lifetime components of eating local)

~ ethics (this includes ecosystem concerns about eating wild plants when they are struggling to survive in reduced habitat)

a patch of Trout Lily in the hardwoods… edible… but should I harvest when this type of habitat is disappearing?

~ barriers to gathering local foods (for example, why do I buy bags of salad greens when Dandelion greens, Violet leaves and Wood-sorrel grow right outside my door?)

In my upcoming posts, I want to explore each of these themes.

~

~

berry picking

~

fingers stain indigo

berry juice as blood

withdrawn by eager

thorns

~

berry picking sticks

to me, burrs

and brambles

hooks and eyes

inseparable as

contentment and picking berries

~

even as I struggle

berries ripen

shake free

fall to ground

~

~

© Jane Tims 2012

Warning: 1. never eat any plant if you are not absolutely certain of the identification; 2. never eat any plant if you have personal sensitivities, including allergies, to certain plants or their derivatives; 3. never eat any plant unless you have checked several sources to verify the edibility of the plant.Wood-sorrel (Oxalis spp.)

When I walk around our property, whether in the woods or in the open areas, I often overlook a little group of plants I am certain grows almost everywhere. The leaves are like those of clover, but the five-petalled flowers of the genus Oxalis are as delicate as any spring wildflower.

I am familiar with two Wood-sorrels, one a plant of the woods and one a plant of more open areas.

Common Wood-sorrel (Oxalis acetosella L.) grows in damp woods. Other names for this plant are Wood-shamrock, Lady’s-sorrel, and, in French, pain de lièvre (literally, rabbit bread). The flowers of Common Wood-sorrel are white with pale red veins and can be found blooming from June to August.

The Yellow Wood-sorrels (Oxalis stricta L. and Oxalis europaea Jord.) are low-growing weeds, found in waste places, along roadsides, in thickets, or in lawns and meadows. The Yellow Wood-sorrels are known by many names, including Lady’s-sorrel, Hearts, Sleeping-Beauty, and, in French, sûrette or pain d’oiseau (bird-bread). The flowers of Oxalis stricta and Oxalis europaea are yellow and bloom May to October. Oxalis stricta and Oxalis europaea are considered separate species, but there is a lot of ambiguity in the various references, probably since both are called Yellow Wood-sorrel. According to Grey’s Botany, Oxalis stricta has a tap-root, whereas Oxalis europeae has spreading and subterranean stolons.

The leaves of both Common and Yellow Wood-sorrels are pale green and clover-like. Each leaf consists of three heart-shaped leaflets. At night, the leaves fold downward.

The generic name oxalis comes from the Greek oxys meaning ‘sour’. The common name ‘sorrel’ comes from the French word for ‘sour’. Leaves of all species of Oxalis have a pleasant, tart taste and can be included in a salad as greens. The leaves are also used in a tea, to be served as a cold drink.

Oxalic acids cause the plants’ sour taste. Use caution ingesting this plant since it can aggravate some conditions such as arthritis, and large quantities can affect the body’s absorption of calcium.

To make a tea and a cold drink from Oxalis leaves, first pick, sort and wash the leaves…

Pour hot water on the leaves. They turn brown instantly! I left the tea to steep for about 10 minutes.

Strain and pour the sorrel-ade over ice cubes. The Wood-sorrel tea makes a pleasant cold drink, with a tart taste and a familiar but elusive flavour. Enjoy!

Warning: 1. never eat any plant if you are not absolutely certain of the identification; 2. never eat any plant if you have personal sensitivities, including allergies, to certain plants or their derivatives; 3. never eat any plant unless you have checked several sources to verify the edibility of the plant.~

~

Common Wood-sorrel

Oxalis montana Raf.

~

Oxalis montana

carpets the grove

three green leaflets

lined in mauve, held low

in folds at night

narrow petals

creamy white, fragile

veins inked in red

Lady’s sorrel

nibbled, sour

rabbit bread

~

~

© Jane Tims 2012

Common Plantain (Plantago major L.)

When we were children, we often pretended to be storekeepers and picked various wild plants as the ‘food’ for sale. We collected weed seeds for our ‘wheat’, clover-heads as ‘ice-cream’, vetch seed pods as ‘peas’, and (gasp) Common Nightshade berries as ‘tomatoes’.

This is probably a good place to urge you to teach your children – everything that looks like a vegetable or fruit may not be good for them to eat! I don’t remember ever trying any of our pretend ‘groceries’, but some of them, such as the Common Nightshade berries, were poisonous and harmful.

berries of Common Nightshade are poisonous… later in the season, they are red and quite beautiful… children should be warned that all red berries are NOT good to eat

We also ‘sold’ the leaves of Common Plantain at our ‘store’. They looked like spinach, and the Plantain leaves would have actually been fine for us to eat.

Common Plantain (Plantago major L.) is a very easily found weed since it grows almost everywhere, especially along roadsides, in dooryards and in other waste places. Plantain is also known as Ribwort, Broad-leaved Plantain, Whiteman’s Foot, or, in French, queue de rat. The generic name comes from the Latin word planta meaning ‘foot’. Major means ‘larger’.

Plantain has thick, dark green, oval leaves. These grow near the ground in a basal rosette. The stems of the leaves are long and trough-like. The leaves themselves are variously hairy and feel rough to the touch. The leaf has large, prominent veins, and, as the plant grows older, these veins become very stringy. The veins resist the breakage of the leaf and stick out from the stem end of a harvested leaf like the strings of celery.

Flowers of Plantain grow in a dense spike on a long, slender stalk rising from the leaves. The flowers are small and greenish-white, appearing from June to August.

The young leaves of Common Plantain can be used in a salad or cooked and seasoned with salt and butter. The older leaves become tough and stringy.

Warning: 1. never eat any plant if you are not absolutely certain of the identification; 2. never eat any plant if you have personal sensitivities, including allergies, to certain plants or their derivatives; 3. never eat any plant unless you have checked several sources to verify the edibility of the plant.

leaves of Common Plantain and Dandelion, picked from our dooryard, not yet washed or looked over for insects… note the strings protruding from the stem ends

Yesterday, I gathered the youngest leaves of plantain I could find and cooked them for my lunch. They might be fine in times of need, but I found the cooked product to be just like eating soggy cardboard.

I should say, since I have begun my almost daily tests of edible wild plants, my husband asks me almost hourly how I am feeling.

~

~

wisdom

~

plantain, past the picking –

a pulled leaf resists,

tethered to a thread

~

~

© Jane Tims 2012

Warning: 1. never eat any plant if you are not absolutely certain of the identification; 2. never eat any plant if you have personal sensitivities, including allergies, to certain plants or their derivatives; 3. never eat any plant unless you have checked several sources to verify the edibility of the plant.Wild Strawberry (Fragaria virginiana Duchesne)

Soon, the fields at our summer place will be jeweled with Wild Strawberries.

Wild Strawberry (Fragaria virginiana Duchesne) grows in open woodlands, fields and barrens. It is also known as Virginia Strawberry, Common Strawberry and, in French, fraisier. The name Fragaria comes from the Latin word for strawberry, fraga meaning fragrance.

The leaves of Wild Strawberry grow on slender stalks, and occur in threes. They are hairy and coarsely toothed. Plants are stoloniferous, meaning they produce ‘stolons’ or runners, freely-rooting basal branches.

The flower of the Wild Strawberry is white, with five petals and numerous stamens and pistils. Right now, our fields are spangled with them. The flowers occur in an open cluster of two or more flowers. In this species, the flower stalk is not longer than the leaf stalk.

The berries are red and ovoid, covered with small pits and seeds. They are more delicate and sweeter than the domestic strawberry. They appear in late June and may last until August, but the best berry-picking is at the first of summer.

In the book ‘The Blue Castle’ by Lucy Maude Montgomery, the heroine says one of her greatest pleasures is to eat berries directly from the stem:

Here they found berries … hanging like rubies to long, rosy stalks. They lifted them by the stalk and ate them from it, uncrushed and virgin, tasting each berry by itself with all its wild fragrance ensphered therein. When Valancy carried any of these berries home that elusive essence escaped and they became nothing more than the common berries of the market-place–very kitchenly good indeed, but not as they would have been, eaten in their birch dell …

(from L.M. Montgomery, The Blue Castle, Chapter 30, McClelland and Stewart Limited, 1972)

~

The berries of the Wild Strawberry are delicious in jam. The leaves also make a fragrant tea, high in Vitamin C. To make the tea, put a handful of green leaves into two cups of boiling water, steep, strain and enjoy!

~

~

too early to pick

~

last week of June

roadside red with leaves

and ripening wild

strawberries hang

still green except

where sepal contrast

shows sweet berry

~

patience, wait

a few days and every berry

ripe and a thimble pot

of berry jam

~

can’t wait?

sour green flesh

grit of tiny seed

~

~

Copyright Jane Tims 2012

Warning: 1. never eat any plant if you are not absolutely certain of the identification; 2. never eat any plant if you have personal sensitivities, including allergies, to certain plants or their derivatives; 3. never eat any plant unless you have checked several sources to verify the edibility of the plant.Sheep Sorrel (Rumex Acetosella L.)

At this time of year, some of the fallow fields adjacent to our Federal-Provincial Agricultural ‘Farm’ in Fredericton are shadowed with bright red. Closer inspection shows these fields are filled with Sheep Sorrel, in scarlet bloom.

The common Sheep Sorrel (Rumex Acetocella L.) is a small, slender plant, less than a foot high, with distinctive leaves shaped a little like an arrowhead or halberd. The lobes at the base of each ‘arrowhead’ leaf point backwards, a shape described in botany as ‘hastate’.

Sheep Sorrel is considered a weed, growing along roadways and in fields. It prefers acidic, ‘sour’ soils and is considered an indicator of these soils.

Sheep Sorrel (Rumex Acetosella ) is also known as Common Sorrel, Field Sorrel, Red Sorrel, and Sour Weed. In French it is called surette or oseille. The old generic name Acetosella means ‘little sorrel’. Sheep Sorrel is from the Buckweat Family of plants.

The flowers of Sheep Sorrel are small, distributed in an open cluster along the stem. The female flowers are maroon and the male flowers are brownish-green.

The leaves of Sheep Sorrel are well-known as an edible plant. They have a pleasantly tart, sour flavour and make a good nibble, an iced tea, or an addition to a salad. They can also be used as a pot-herb – when cooked they reduce in size like spinach, and they lose the acid taste. The Sheep Sorrel plant has a chemical called oxalate so cannot be consumed in large quantities. Long-term consumption can affect calcium absorption in the body. As always, please be sure of your identification before you consume any wild plant.

Warning: 1. never eat any plant if you are not absolutely certain of the identification; 2. never eat any plant if you have personal sensitivities, including allergies, to certain plants or their derivatives; 3. never eat any plant unless you have checked several sources to verify the edibility of the plant.~

~

red field

~

walk in the field with the scarlet flowers

arrowheads and halberds surely leave

a sour taste on the tongue

titration with alkaline needed

to sweeten the ground, dilute the red

return the soil

to more productive ways

~

~

© Jane Tims 2012

keeping watch for dragons #6 – Water Dragon

The last full week in May, we took a day to drive the Plaster Rock-Renous Highway. This is an isolated, but paved, stretch of road, called Highway 108, connecting the sides of the province through a large, unpopulated area. The highway runs from Plaster Rock in the west, to Renous in the east and traverses three counties, Victoria, York and Northumberland. It takes you across more than 200 km of wetland, hardwood, and mixed coniferous forest, some privately owned, and some Crown Land. A large part of the area has been clearcut, but the road also passes through some wilderness of the Plaster Rock-Renous Wildlife Management Area and the headwaters of some of our most beautiful rivers.

From the east, the highway first runs along the waters of the Tobique River, across the Divide Mountains, and into the drainage of the Miramichi River, crossing the Clearwater Brook, and running along the South Branch of the Dungarvon River and the South Branch Renous River.

Along the way, we stopped at a boggy pond next to the road between Clearwater Brook and the Dungarvon, to listen to the bull frogs croaking. There among the ericaceous vegetation filling most of the pond was a dragon for my collection.

look closely near the center of the photo… the single white spot is the spathe of a Wild Calla or Water Dragon

Water Dragon, more commonly known as Wild Calla or Water Arum, was present in the shallow, more open waters of the pond, appearing as startling white spots on an otherwise uniform backdrop of green and brown.

Wild Calla (Calla palustis L.) is also known as Female Dragons, Frog-cups, Swamp-Robin and, in French, calla des marais, arum d’eau, or aroïde d’eau. It lives in wet, cold bogs, or along the margins of ponds, lakes and streams.

The Wild Calla belongs to the Arum family, along with Jack-in-the-Pulpit (Arisaema Stewardsonii Britt.) and Skunk Cabbage (Symplocarpus foetidus (L.) Nutt.). These plants have tiny flowers along a thick spike known as a ‘spadix’. The spadix is enclosed by a leafy bract called the ‘spathe’. The spathe of Wild Calla is bright white, ovoid and abruptly narrow at the tip. The leaves are glossy green and heart-shaped. The flowers growing among them are often overlooked. On the pond, there were about ten visible spathes, and likely many more hidden among the plentiful leaves.

The various parts of the Wild Calla are considered poisonous since they contain crystals of calcium oxalate. These cause severe irritation of the mouth and throat if eaten. However, there is a twist to this story of a poisonous plant. Scandanavian people, in times of severe hardship, prepared flour for ‘Missen bread’ from the dried, ground, bruised, leached, and boiled seeds and roots of Wild Calla. Do I have to warn you not to try this at home!!!!????

Warning: 1. never eat any plant if you are not absolutely certain of the identification; 2. never eat any plant if you have personal sensitivities, including allergies, to certain plants or their derivatives; 3. never eat any plant unless you have checked several sources to verify the edibility of the plant.Linnaeus, the botanist who invented the binomial (Genus + Species) method of naming plants, described the laborious process the Swedish people used to remove the poisonous crystals from the Water Dragon in order to make flour. To read Linnaeus’ account, see Mrs. Campbell Overend, 1872, The Besieged City, and The Heroes of Sweden (William Oliphant and Co., Edinburgh), page 132 and notes (http://books.google.ca/books?id=IAsCAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA222&lpg=PA222&dq=missen+bread&source=bl&ots=ZO8cl_2nBl&sig=Gtr5Lq6PvG3DXV_l-kfECNuhWfo&hl=en&sa=X&ei=gGLFT-79B4OH6QG1m-nOCg&ved=0CC8Q6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=missen%20bread&f=false Accessed May 29, 2012).

~

~

~

desperate harvest

‘… they can be satisfied with bark-bread, or cakes made of the roots of water-dragon, which grows wild on the banks of the river…’

– Mrs Campbell Overend, 1872

~the pond beside the road

simmers, a kettle

of frog-croak and leather-leaf

~

spathes of Water Dragon

hug their lamposts, glow white

lure the desperate to the pond

~

bull-frog song deepens the shallows

the way voices lower when they speak

of trouble, of famine

~

people so hungry, harvest so poor

they wade in the mire

grind roots of Wild Calla for flour

~

needles to the tongue

burns to the throat

crystals of calcium oxalate, poison

~

worth the risk –

the drying,

the bruising,

the leaching,

the boil,

the painful test to know

if poison has been neutralized

~

the toughness of

the Missen bread

~

~

© Jane Tims 2012

Warning: 1. never eat any plant if you are not absolutely certain of the identification; 2. never eat any plant if you have personal sensitivities, including allergies, to certain plants or their derivatives; 3. never eat any plant unless you have checked several sources to verify the edibility of the plant.wildflowers in the rich spring hardwoods

On our drive and hike along the South Branch Dunbar Stream, north of Fredericton, we encountered many spring wildflowers. The Trout Lily (Erythronium americana Ker) was everywhere, in extensive carpets, especially in hummocky areas (see my post for June 1, 2012). The delicate Wood Anemone was just beginning its bloom, also in dense carpets of feathery foliage. Other plants in these woods included the Purple Trillium and Green Hellebore.

The Wood Anemone (Anemone quinquefolia L.) is one of our less common plants. Its leaves are deeply toothed with 3 to 5 parts. The ‘flower’ is white and five-petalled, not really a flower at all, but the white sepals of the plant.

The Purple Trillium (Trillium erectum L.), also known as the Wakerobin, is a showy plant with the parts in three’s. The flower is maroon or purple, and, as in our case, may be nodding, in spite of the name (erectum meaning erect). The flower is known by its purple ovary (female part of the flower) and its nasty odor. You can eat the very young leaves of the Purple Trillium, but they are not usually in large abundance, so to protect the plants, I recommend just enjoying their bloom.

The light green leaves of Green or False Hellebore (Veratrum viride Ait.) were also conspicuous in the woods, I see them in woods along rivers all over our area. They are large plants, made up of heavily ribbed, pleated, clasping leaves. The leaves are parallel veined and do not smell like skunk, unlike the Skunk-Cabbage which has netted veins in the leaves and a skunky odor. Later, the Green Hellbore will have large clusters of yellow-green star-shaped flowers. This plant is poisonous.

We enjoyed our hike, and saw a beaver tending his dam and a narrow, raging waterfall pouring into the South Branch of the Dunbar, probably only a trickle in summer after the heavy spring rains are gone.

~

© Jane Tims 2012

Trout-lily (Erythronium americanum Ker)

Two weeks ago, we had a memorable drive and hike along the South Branch Dunbar Stream, north of Fredericton. The wet hardwoods along the intervale areas of the stream were green with understory plants and dotted with spring wildflowers. One of the plants growing there in profusion is the Trout Lily. The Trout Lily is colonial, covering slopes in rich, moist hardwoods. Its red and green mottled leaves grow thick on the hummocks, beside the Wood Anemone and Purple Trillium. The area where we were hiking was not far from the stream and there was evidence it had been flooded earlier in the year.

Trout Lily (Erythronium americanum Ker) is also known as the Dog’s Tooth Violet, Yellow Adder’s-tongue, Fawn-lily, and, in French, ail doux. Its generic name is from the Greek erythros meaning ‘red’, a reference to the purple-flowered European species.

The Trout Lily was barely beginning its blooming when we were there, but it will be almost over by now. The flowers usually bloom from March to May. They are yellow and lily-like, with six divisions. The petals curve backward as they mature.

The young leaves are edible but should only be gathered if they are very abundant in order to conserve the species. To prepare the leaves for eating, clean them, boil them for 10 to 15 minutes and serve with vinegar. The bulb-like ‘corm’ is also edible; it should be cooked about 25 minutes and served with butter. Again, the bulbs should only be gathered if the plant is very plentiful, and only a small percentage of the plants should be harvested to enable the plant to thrive. Also, the usual warning applies, only harvest if you are absolutely certain of the identification.

~

~

Trout Lily

(Erythronium americanum Ker)

~

on a hike in the hardwood

north of the Dunbar Stream

you discover Trout Lily in profusion

mottled purple, overlapping

as the scales of adder, dinosaur or dragon

~

you know these plants as edible

the leaves a salad, or pot-herb

and, deep underground, the corm

flavoured like garlic

~

you fall to your knees

to dig, to gather

and hesitate,

examine your motives –

you, with two granola bars in your knapsack

and a bottle of water from Ontario

~

~

© Jane Tims 2012

Warning: 1. never eat any plant if you are not absolutely certain of the identification; 2. never eat any plant if you have personal sensitivities, including allergies, to certain plants or their derivatives; 3. never eat any plant unless you have checked several sources to verify the edibility of the plant.